Of the unsolved problems in math, there are plenty that have garnered the attention of the public in the large. Generally speaking, math being the esoteric subject it is, the famous-ness of an unsolved math problem doesn’t seem to be directly correlated to how easy its statement is to understand. The Clay Mathematics Institute has long held a list of problems, the Millennium Prize Problems, which have garnered some attention, but they tend to be too specific and technical to really capture the attention of most. To wit, the only problem on the list solved so far, The Poincare Conjecture, is introduced:

In 1904 the French mathematician Henri Poincaré asked if the three dimensional sphere is characterized as the unique simply connected three manifold. This question, the Poincaré conjecture, was a special case of Thurston’s geometrization conjecture. Perelman’s proof tells us that every three manifold is built from a set of standard pieces, each with one of eight well-understood geometries.

Now, for someone like me, this is one of the most astounding things to read: the Poincare Conjecture finally solved?! I was giddy when it happened, to be sure. But I will forgive you if it doesn’t ruffle your lace. The Clay challenge problems represent the frontiers of mathematics in the sense that we have our theorems as far as they are able to go, and work continues with new ideas being tested all the time. There is a massive body of mathematics sitting underneath all current attempts to rectify any of the given problems on that list, and this body is nearly corporeal in its ability to stifle the attempts of the casual math enthusiast.

However, always, what really scares us is what we fail to mention. And there is a problem that isn’t and will not be on the Clay list that is truly frightening.

Let’s play a game. The rules are as follows: a positive integer is picked. If the number is even, we will simply half it. If the number is odd, we will multiply it by 3 and add one. Whatever number is produced by these efforts, we will iterate the process again; halving if the number is even and tripling and increasing by one otherwise. We continue doing this until something interesting happens.

For example, if we pick the number 8, since it’s even, we would get a chain of events:

8 → 4 → 2 →1

and since 1 is odd, we triple it and add 1:

1 → 4

But notice now that we have a loop

4 → 2 → 1 →4 →2 → 1 → …

Mathematicians would say we have found a closed orbit. Let’s see if there are any more...shall we start with an odd number?

5 → 16 → 8 →4 → 2 →1

Huh. That’s cool. What if I start with another odd number?

7 → 22 → 11 → 34 → 17 →52 →26 →13 → 40 →20 →10 → 5 →… →1

Wow! What a coincidence. What’s popping out at me immediately is that 7 is a much smaller odd number than 17, and yet 17 is closer to the closed orbit in this sequence than 7 is. Similarly,

3 → 10 → 5 → … → 1

is a short sequence starting at a smaller odd number that doesn’t even appear on the sequence starting at 7. What is going on here? It’s reasonable to ask two questions:

- is there a pattern to all of this that can be predicted?

- Does this eventual behavior hold for all positive integers? That is, no matter what number you start with, does it eventually reach 1?

Notice that the answer to question 1 would provide insight into 2, while it may be possible to know the answer to the second question without completely understanding the first.

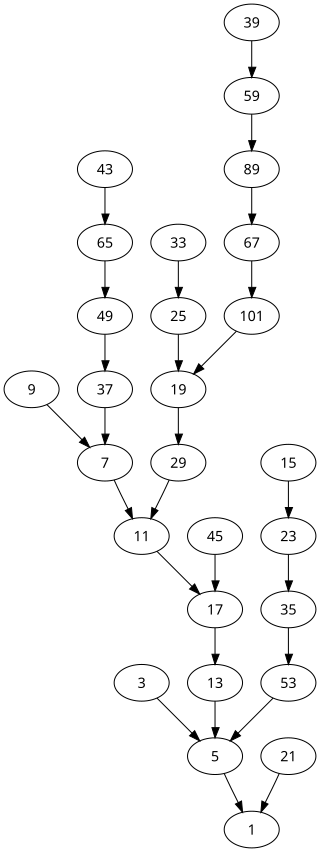

To give us some insight into these questions, let’s consider some more computations. In the tree below, even numbers are omitted as they “collapse” onto odd numbers in a predictable fashion.

There are a few things to notice about this tree. One of them is the overall lack of a cohesive pattern in its appearance. Numbers seem to be somewhat arbitrarily connected to one another on this list, in ways that aren’t obvious from properties such as their divisors, whether they are prime, and so on. Indeed, this is a typical picture of what’s now become known as the Collatz Problem, named after Lothar Collatz for whom the problem became popularized.

The Collatz Conjecture is that any positive integer one picks will eventually arrive at 1 under this process. It’s a conjecture and not a theorem; that is, it is currently unknown whether this is a true or a false statement in arithmetic. Its wikipedia entry is very suitable as an introduction to the major advancements on the topic, as well as some of the beautiful visualizations the problem has inspired. Of note is the statement:

As of 2020, the conjecture has been checked by computer for all starting values up to 2^68...

That’s a lot of numbers, it’s on the order of 3 followed by 20 zeros. It’s nearly impossible for the human experience to appreciate such a number and, even still, this does not settle the Collatz Conjecture. To properly put this one to bed, we would need a proof that’s applicable to all positive integers. In mathematics, empirical evidence isn’t proof.

(What’s worse is that truth isn’t proof, even in mathematics, so we need to be careful here. More on that later.)

The Collatz Conjecture may be true, it may be false. There is certainly precedence in mathematics for statements failing only for very large numbers. What makes the Collatz Conjecture notable is the ease with which it is stated and its ostensible difficulty. It is, in my opinion, the current reigning champion of hard math problems. Paul Erdos, famous for his superhuman problem-solving abilities, was once said to have remarked that mathematics is “not ready” for the Collatz conjecture.

It is so hard, there aren’t a lot of ways that mathematicians have found to approach it. The theoretical framework that makes the most sense to couch it in is the study of Dynamical Systems, which is simply a fancy-pants way of saying “things that change their state in time”. In a subsequent post, I will discuss some approaches to the Collatz Conjecture and talk about some advancements that have been made. I will try to explain why it’s so hard and what can be done about it, if anything at all.

Who knows, maybe you’ll be the one to solve it?