Introduction

Morse Theory, named after the mathematician Marston Morse, is a powerful mathematical tool that connects the critical points of a smooth function on a manifold with the topology of the manifold itself. Originally developed in the 1920s, Morse Theory has since become a cornerstone of differential topology, providing deep insights into the structure and behavior of complex systems.

Raoul Bott, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century, expanded and refined Morse Theory, applying it to a wide range of mathematical fields. His work on the Bott periodicity theorem and Morse Theory has left a lasting legacy, shaping the way mathematicians understand the relationship between geometry and topology. In his talk, "Morse Theory Indomitable", Bott emphasized the enduring relevance of Morse Theory, highlighting its applicability to both classical and modern mathematical problems.

Before exploring the interplay of Morse Theory and causal networks, it's important to understand the concept of directed graphs, which are fundamental to this discussion. A directed graph, or digraph, is a set of points (called vertices or nodes) connected by arrows (called edges) that have a direction. These arrows indicate the direction of influence or flow from one node to another. Directed graphs are used to model systems where the relationship between elements is directional, such as the flow of information, the progression of time, or causal relationships. You can think of them as a roadmap where each intersection (node) is connected by one-way streets (edges) that dictate how traffic flows from one point to another. For more details, you can refer to the Wikipedia page on directed graphs.

In my previous article, Morse Theory and the Geometry of Bioelectric Morphology, I examined the intersection of Morse Theory with the bioelectric fields that guide the development and morphogenesis of living organisms. Building on this foundation, I now turn my attention to a broader and more abstract framework: causal networks, and the role Morse Theory plays in understanding the structure and dynamics of these networks.

This continuation draws heavily on the insights of Bott’s work, as well as the conversation between Rupert Sheldrake and David Bohm regarding nonlocality and morphic resonance. It also builds upon the ideas I introduced in my article, "Classical to Quantum: Causal Networks and the Emergence of Nonlocality", where I explored how classical causal structures can give rise to quantum phenomena through the lens of nonlocality.

In that work, I examined how the transition from classical to quantum realms could be understood as a shift in the topological structure of causal networks, where nonlocal connections become increasingly prominent. This current exploration takes those ideas further by considering how Morse Theory and simplicial complexes can provide a rigorous mathematical framework for understanding the dynamics of these networks, and how nonlocality arises as a natural consequence of their topological properties.

Causal Structures and Directed Graphs

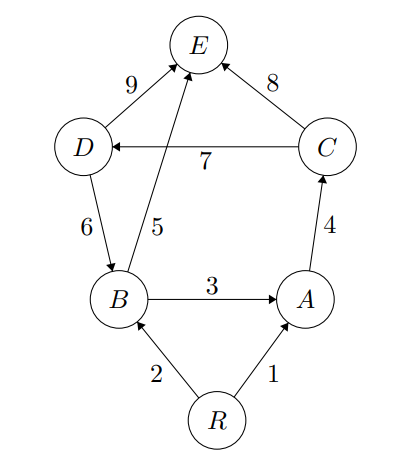

At the core of our exploration lies the concept of a causal structure, a directed graph characterized by a single root with paths extending to every other node within the graph. This root serves as the origin, the point from which all causal relationships in the system emanate. The structure of such a graph reflects the underlying architecture of numerous processes, ranging from biological development to quantum mechanical phenomena.

In a causal structure, the directed edges represent the flow of influence or information from one node to another, often capturing the direction of time, cause-and-effect relationships, or hierarchical dependencies. The requirement that every node be reachable from the root ensures that the system is connected, implying that no part of the system is isolated from the initial cause or starting point. This reachability is crucial, as it ensures that all parts of the system are influenced by, and can potentially influence, the root, creating a dynamic interplay of cause and effect throughout the structure.

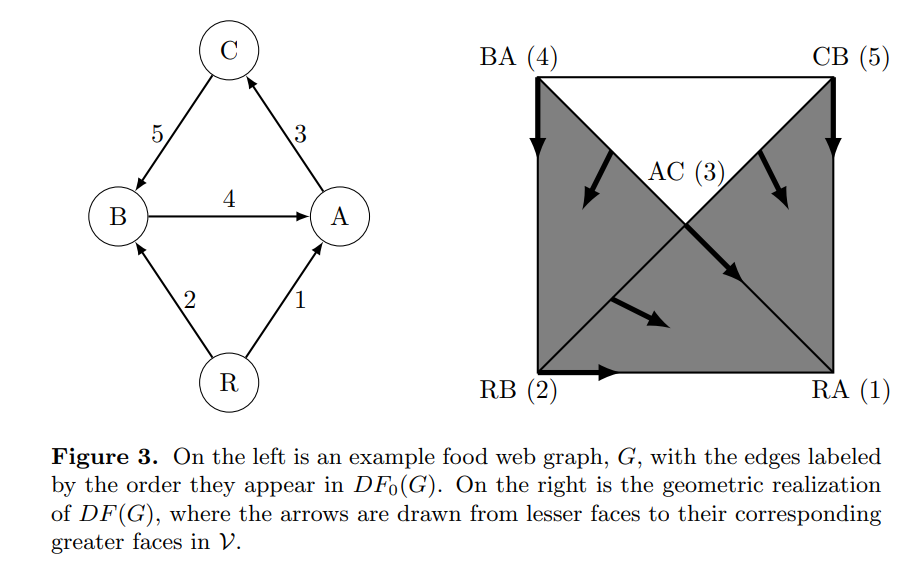

The dynamics within these graphs can be understood through the lens of Morse flow, which acts as a potential energy guiding the movement or "traffic" within the phase space of the graph. The Morse function, defined over the graph, assigns values to each node, creating a topological landscape where the flow naturally moves from regions of higher potential to lower potential, much like how objects move under the influence of gravity. This flow is not static; it creates the topology by determining the critical points—places where the potential changes most significantly, directing the flow from one region to another.

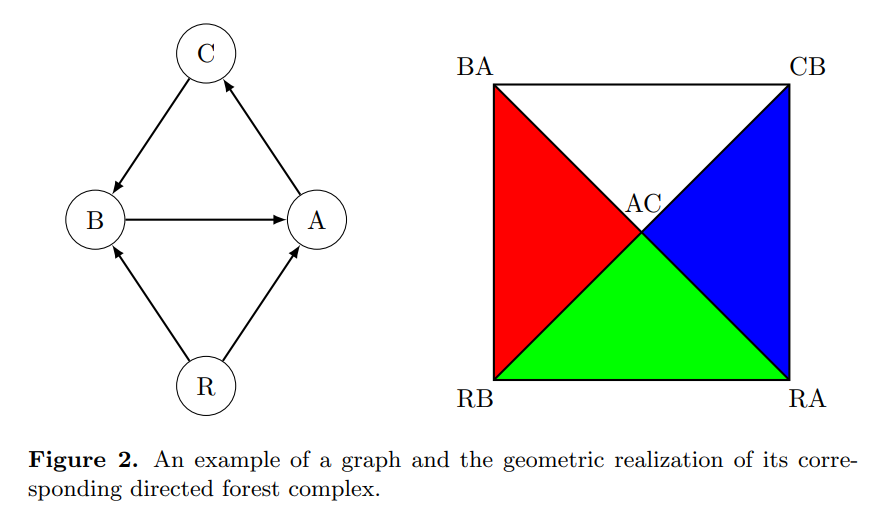

The analysis of such structures becomes particularly rich when we consider the Directed Forest Complex associated with a causal structure. A directed forest complex is an abstract simplicial complex where each simplex corresponds to a collection of edges forming disjoint, directed trees within the original graph. These trees, being acyclic, represent substructures of the causal network that maintain a strict hierarchy, devoid of feedback loops or cycles.

Topologically, the directed forest complex of a causal structure can be understood as a "wedge" of spheres. This means that, when we examine the complex from a topological perspective, it behaves as if it were composed of multiple spheres that are joined together at a common point. Each sphere in this wedge corresponds to a particular tree-like structure within the causal network, representing a stable, hierarchical substructure. The idea of a wedge of spheres provides a powerful visualization tool: just as soap bubbles cluster together to form a coherent whole, the spheres in the directed forest complex come together to define the overall topology of the causal network.

It’s essential to note that the directed forest complex is actually a collection of abstract simplicial complexes—in simpler terms, it’s like a bunch of multidimensional triangles glued together. These simplices, ranging from 0-simplices (points) to higher-dimensional ones (edges, triangles, tetrahedra, etc.), are the building blocks that make up the complex. This gluing together of simplices encodes the topological relationships between the various parts of the causal structure, providing a rich and nuanced understanding of its geometry.

The Morse flow within these graphs is what gives rise to their dynamism, transforming the directed forest complex from a static structure into a phase space where the potential energy dictates the movement through the complex. By analyzing this flow, we gain insights into how different regions of the network influence each other, how stability is maintained, and where transitions or bifurcations might occur.

This wedge structure has profound implications for understanding how information or influence propagates through the network. The boundaries between the spheres, akin to the interfaces between soap bubbles, represent the potential for interaction or transition between different stable states or regions within the network. These transitions are governed by the underlying topology, which dictates how the different regions of the network can connect and influence each other.

By analyzing the directed forest complex of a causal structure, we can begin to understand the constraints and possibilities inherent in the network. The topological properties of the complex reveal the fundamental pathways through which influence can travel, the points of stability, and the critical junctures where change or divergence can occur. This analysis provides a framework for understanding both the static structure of the network and its dynamic behavior, as the system evolves over time, guided by the flow of potential energy.

The Topology of Soap Bubbles

To grasp the abstract topology of the directed forest complex, consider the metaphor of soap bubbles. When soap bubbles cluster together, they form intricate, multi-faceted structures, with each bubble representing a distinct yet interconnected entity. Similarly, the directed forest complex can be viewed as a topological structure composed of multiple "bubbles"—specifically, spheres that represent stable configurations within a causal network.

(Here, the white triangle on the right is void, leaving a one-dimensional "bubble")

However, these "bubbles" are more than just spheres in the everyday sense; they are topological objects that can be understood as multi-dimensional simplices, or higher-dimensional triangles. In the context of the directed forest complex, these simplices are glued together along their faces, creating a complex structure that encodes the relationships between different parts of the causal network. Each simplex, whether it’s a point, an edge, a triangle, or a higher-dimensional analog, represents a fundamental building block of this topological space.

When we describe the directed forest complex as a "wedge" of spheres, we’re referring to how these simplices come together to form a cohesive topological entity. The wedge itself is formed by taking multiple spheres (or, in higher dimensions, their analogs) and joining them at a common point, much like how soap bubbles meet at their interfaces. The result is a structure that, while composed of individual, stable "bubbles," also contains the potential for complex interactions at the points where these bubbles meet.

The Morse flow plays a crucial role in this context, acting as the potential energy that directs how these "bubbles" or simplices interact. Just as soap bubbles adjust and deform based on surface tension, the Morse flow guides the movement within the directed forest complex, determining how the system evolves over time. This flow defines the topology of the complex, creating regions of stability and points of transition where the structure of the network might change.

These interfaces between bubbles, or in our case, the simplices within the directed forest complex, are where the most interesting topological phenomena occur. The "tension" at these interfaces is not a physical tension but rather a topological one. It represents the constraints and possibilities inherent in the way the simplices are glued together. In a causal network, this tension could correspond to the potential for transitions between different states, much like how soap bubbles can merge or separate at their boundaries.

(Here, the one-dimensional bubble represented by the void on the right is exerting its influence throughout the entire structure of the directed forest complex via the Morse Flow.)

This topological tension is a powerful metaphor for understanding nonlocality in quantum systems. Just as the structure of a soap bubble cluster is influenced by the tension at the interfaces, the nonlocal connections in a quantum system can be thought of as arising from the topological structure of the network. These nonlocal connections, which may appear as "jumps" or sudden transitions in the network, are encoded in the way the simplices of the directed forest complex are arranged and interact.

By examining the topology of these "soap bubbles" within the directed forest complex and understanding the Morse flow that directs their interaction, we can gain insights into the underlying structure of causal networks, the stability of their configurations, and the nature of the transitions between them. This topological perspective provides a deeper understanding of how complex systems evolve, interact, and maintain coherence, even in the presence of potentially disruptive nonlocal connections.

Nonlocality and the Sheldrake-Bohm Conversation

The concept of nonlocality, where connections and influences extend beyond the immediate, conventional paths of interaction, is a cornerstone of many discussions in modern physics, particularly in quantum mechanics. Rupert Sheldrake and David Bohm explored this idea in their conversation on morphic fields and quantum phenomena, proposing that nonlocal connections might underlie the very fabric of reality. In the context of our exploration of causal structures and simplicial complexes, nonlocality emerges as a natural consequence of the topological structure of these systems.

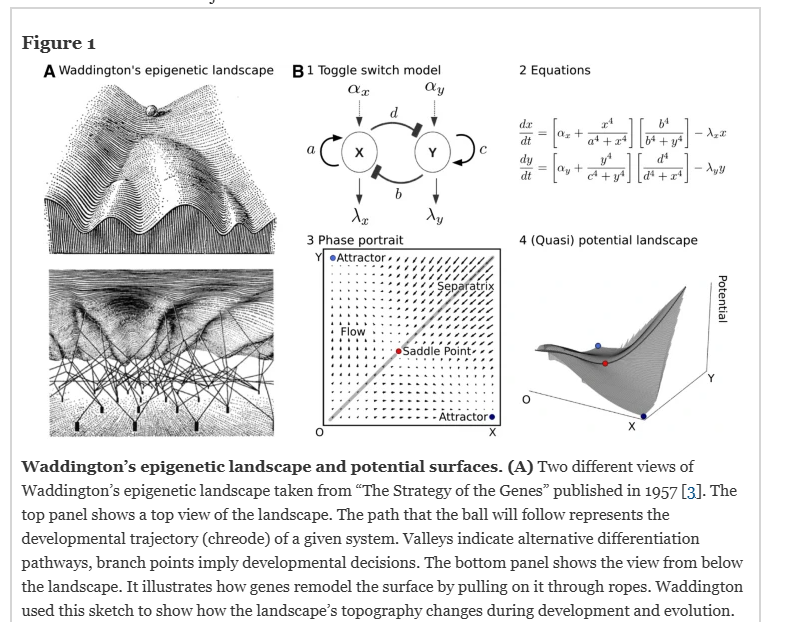

In biological development, the concept of creodes—stable pathways within an organism's epigenetic landscape—plays a crucial role in understanding how tissues and organs form. Creodes represent the trajectories that cells follow as they differentiate, effectively functioning as causal structures within the developmental process. These creodes can be visualized as directed graphs where nodes represent key developmental states and edges signify transitions or influences between these states.

The idea of creodes aligns with the concept of morphic fields proposed by Sheldrake, where patterns or forms are influenced by similar patterns or forms from the past. The paper by Mahadevan et al., "Classification of transient behaviours in a time-dependent toggle switch model", explores how these pathways can be mapped and understood using topological methods. This approach provides a deeper understanding of how creodes interact within the broader developmental landscape, contributing to the formation of complex structures such as organs.

Source: Mahadevan et al.

In this context, organs can be viewed as directed forest complexes formed from the interaction of these creodes. Each organ's shape and function emerge from the topological interaction of these underlying causal structures, where the directed forest complex acts as a blueprint, guiding the overall morphology and ensuring that the organ forms correctly.

Sheldrake’s idea of morphic resonance, where patterns or forms are influenced by similar patterns or forms that have occurred before, can be seen as a manifestation of this topological nonlocality. The simplicial complex provides a mathematical framework for understanding how these influences can extend beyond the immediate, local environment of a system. Just as the structure of the complex dictates the potential paths of interaction, the morphic field shapes the potential for certain patterns or behaviors to emerge based on previous configurations.

Bohm’s idea of the implicate order, where everything is interconnected in a deep, underlying way, also resonates with this topological perspective. The simplicial complex, with its intricate web of connections and potential interactions, can be seen as a manifestation of this implicate order. Nonlocality, in this context, is not merely a feature of quantum mechanics but a fundamental property of the topological structure of reality as described by the directed forest complex.

These ideas are further explored and elaborated in my preprint, "The Topology of Awareness: Mapping the Holographic Terrain of Conscious Experience", where I apply the framework of simplicial complexes to model the structure and dynamics of consciousness. In this work, I introduce the concept of "Conscious Experience Graphs" and "Simplicial Complexes of Conscious Experiences" to represent the web of relationships and transformations between different states of awareness. By leveraging the tools of discrete Morse theory, I explore how the critical simplices within these complexes correspond to essential or irreducible states of awareness, while the homological perspective reveals the topological features that characterize the structure of subjective experience.

Thus, the discussion between Sheldrake and Bohm finds a concrete mathematical expression in the simplicial complexes formed by causal structures. Nonlocality, in this view, is a natural outcome of the way these complexes are built and interact. The directed forest complex, with its multidimensional simplices and the Morse flow guiding their interaction, provides a powerful framework for understanding how influences can propagate across the system in ways that transcend traditional, local interactions. This framework has profound implications for our understanding of consciousness and reality itself.

Conclusion

The application of Morse Theory to the study of causal networks reveals the deep interplay between topology and dynamics in complex systems. By understanding these networks as simplicial complexes, we gain insight into how nonlocality and resonance emerge naturally from their structure. The Morse flow acts as the potential energy that directs traffic within these networks, shaping the pathways through which information and influence propagate.

Through the lens of Morse Theory, we see that the tension at the interfaces within these networks—akin to the tension at the boundaries of soap bubbles—creates the conditions for nonlocal effects. These effects, which are often seen as mysterious or paradoxical, can be understood as topological features of the network, where connections between distant parts of the system are facilitated by the underlying structure of the simplicial complex.

This perspective not only provides a rigorous mathematical framework for describing nonlocality in causal systems but also offers a way to conceptualize the dynamics of consciousness and awareness. As explored in my preprint, "The Topology of Awareness: Mapping the Holographic Terrain of Conscious Experience", the tools of discrete Morse theory and simplicial complexes can be applied to model the structure and dynamics of conscious experience, revealing the topological features that characterize our subjective reality.

In conclusion, the integration of Morse Theory with causal networks and simplicial complexes provides a powerful framework for understanding the interconnectedness of complex systems. Whether in the context of quantum mechanics, biological morphogenesis, or consciousness studies, these ideas offer profound insights into the nature of reality, highlighting the importance of topology in shaping the behavior and evolution of complex networks.